Migration to Google Cloud Platform — gRPC & grpc-gateway

Our guest post today comes from Miguel Mendez of Yik Yak.

This post was originally a part of the Yik Yak Engineering Blog which focused on sharing the lessons learned as we evolved Yik Yak from early-stage startup code running in Amazon Web Services to an eventual incremental rewrite, re-architecture, and live-migration to Google Cloud Platform.

In our previous blog post we gave an overview of our migration to Google Cloud Platform from Amazon Web Services. In this post we will drill down into the role that gRPC and grpc-gateway played in that migration and share some lessons which we picked up along the way.

Most people have REST APIs, don’t you? What’s the problem?

Yes, we actually still have REST APIs that clients use because migrating the client APIs was out of scope. To be fair, you can make REST APIs work and there are a lot of useful REST APIs out there. Having said that, the issues that we had with REST lie in the details.

No Canonical REST Specification

There is no single REST specification that is canonical. There are best practices, but no true canon. For that reason, there isn’t unanimous agreement on when to use specific HTTP methods and response codes. Beyond that, not all of the possible HTTP methods and response codes are supported across all platforms… This forces REST API implementers to compensate for these deficiencies using techniques that work for them but create more variance in REST APIs across the board. At best, REST APIs are really REST-ish dialects.

Harder on Developers

REST APIs aren’t exactly great from a developer’s standpoint either. First, because REST is tied to HTTP there is no simple mapping to an API in my language of choice. If I’m using Go or Java there is no “interface” that I can use in my code to stub it out. I can create one, but it is extra-linguistic to the REST API definition.

Second, REST APIs spread information that is necessary to interpreting the intent of the request across various components of the request. You have the HTTP method, the request URI, the request payload, and it can get even more complicated if request headers are involved in the semantics.

Third, it is great that I can use curl from the command line to hit an API, but it comes at the cost of having to shoehorn the API into that ecosystem. Normally that use case only matters for letting people quickly try out an API — and if that is high on your list of requirements then by all means feel free to use REST… Just keep it simple.

No Declarative REST API Description

The fourth problem with a REST APIs is that, at least until Swagger arrived on the scene, there was no declarative way to define a REST API and include type information. It may sound pedantic, but there are legitimate reasons to want a proper definition that includes type information in general. To reinforce the point, look at the lines of PHP server code below, which were extracted from various files, that set the “hidePin” field on “yak” which was then returned to the client. The actual line of code that executed on the server was a function of multiple parameters, so imagine that the one which was run was basically chosen at random:

// Code omitted…

$yak->hidePin=false;

// Code omitted…

$yak->hidePin=true;

// Code omitted…

$yak->hidePin=0;

// Code omitted…

$yak->hidePin=1;

What is the type of the field hidePin? You cannot say for certain. It could be a boolean or an integer or whatever happens to have been written there by the server, but in any case now your clients have to be able to deal with these possibilities which makes them more complicated.

Problems can also arise when the client’s definition of a type varies from that which the server expects. Have a look at the server code below which processed a JSON payload sent up by a client:

// Code omitted…

switch ($fieldName) {

// Code omitted…

case “recipientID”:

// This is being added because iOS is passing the recipientID

// incorrectly and we still want to capture these events

// … expected fall through …

case “Recipientid”:

$this->yakkerEvent->recipientID = $value;

break;

// Code omitted…

}

// Code omitted…

In this case, the server had to deal with an iOS client that sent a JSON object whose field name used unexpected casing. Again, not insurmountable but all of these little disconnects compound and work together to steal time away from the problems that really move the ball down the field.

gRPC can address the issues with REST…

If you’re not familiar with gRPC, it’s a “high performance, open-source universal remote procedure call (RPC) framework” that uses Google Protocol Buffers as the Interface Description Language (IDL) for describing a service interface as well as the structure of the messages exchanged. This IDL can then be compiled to produce language-specific client and server stubs. In case that seemed a little obtuse, I’ll zoom into the aspects that are important.

gRPC is Declarative, Strongly-Typed, and Language Independent

gRPC descriptions are written using an Interface Description Language that is independent of any specific programming language, yet its concepts map onto the supported languages. This means that you can describe your ideal service API, the messages that it supports, and then use “protoc”, the protocol compiler, to generate client and server stubs for your API. Out of the box, you can produce client and server stubs in C/C++, C#, Node.js, PHP, Ruby, Python, Go and Java. You can also get additional protoc plugins which can create stubs for Objective-C and Swift.

Those issues that we had with “hidePin” and “recipientID” vs.”Recipientid” fields above go away because we have a single, canonical declaration that establishes the types used, and the language-specific code generation ensures that we don’t have typos in the client or server code regardless of their implementation language.

gRPC Means No hand-rolling of RPC Code is Required

This is a very powerful aspect of the gRPC ecosystem. Often times developers will hand roll their RPC code because it just seems more straightforward. However, as the number of types of clients that you need to support increases, the carrying costs of this approach also increase non-linearly. Imagine that you start off with a service that is called from a web browser. At some point down the road, the requirements are updated and now you have to support Android and iOS clients. Your server is likely fine, but the clients now need to be able to speak the same RPC dialect and often times there are differences that creep in. Things can get even worse if the server has to compensate for the differences amongst the clients. On the other hand, using gRPC you just add the protocol compiler plugins and they generate the Android and iOS client stubs. This cuts out a whole class of problems. As a bonus, if you don’t modify the generated code — and you should not have to — then any performance improvements in the generated code will be picked up.

gRPC has Compact Serialization

gRPC uses Google protocol buffers to serialize messages. This serialization format is very compact because, among other things, field names are not included in the serialized form. Compare this to a JSON object where each instance of an object carries a full copy of its field names, includes extra curly braces, etc. For a low-volume application this may not be an issue, but it can add up quickly.

gRPC Tooling is Extensible

Another very useful feature of the gRPC framework is that it is extensible. If you need support for a language that is not currently supported, there is a way to create plugins for the protocol compiler that allows you to add what you need.

gRPC Supports Contract Updates

An often overlooked aspect of service APIs is how they may evolve over time. At best, this is often a secondary consideration. If you are using gRPC, and you adhered to a few basic rules, your messages can be forward and backward compatible.

Grpc-gateway — because REST will be with us for a while…

You’re probably thinking: gRPC is great but I have a ton of REST clients to deal with. Well, there is another tool in this ecosystem and it is called grpc-gateway. Grpc-gateway “generates a reverse-proxy server which translates a RESTful JSON API into gRPC”. So if you want to support REST clients you can, and it doesn’t cost you any real extra effort. If your existing REST clients are pretty far from the normal REST APIs, you can use custom marshallers with grpc-gateway to compensate.

Migration and gRPC + grpc-gateway

As mentioned previously, we had a lot of PHP code and REST endpoints which we wanted to rework as part of the migration. By using the combination of gRPC and grpc-gateway, we were able to define gRPC versions of the legacy REST APIs and then use grpc-gateway to expose the exact REST endpoints that clients were used to. With these alternative implementations in place we were able to move traffic between the old and new systems using combinations of DNS updates as well as our Experimentation and Configuration System without causing any disruption to the existing clients. We were even able to leverage the existing test suites to verify functionality and establish parity between the old and new systems. Lets walk through the pieces and how they fit together.

gRPC IDL for “/api/getMessages”

Below is the gRPC IDL that we defined to mimic the legacy Yik Yak API in GCP. We’ve simplified the example to only contain the “/api/getMessages” endpoint which clients use to get the set of messages centered around their current location.

// APIRequest Message — sent by clients

message APIRequest {

// userID is the ID of the user making the request

string userID = 1;

// Other fields omitted for clarity…

}

// APIFeedResponse contains the set of messages that clients should

// display.

message APIFeedResponse {

repeated APIPost messages = 1;

// Other fields omitted for clarity…

}

// APIPost defines the set of post fields returned to the clients.

message APIPost {

string messageID = 1;

string message = 2;

// Other fields omitted for clarity…

}

// YYAPI service accessed by Android, iOS and Web clients.

service YYAPI {

// Other endpoints omitted…

// APIGetMessages returns the list of messages within a radius of

// the user’s current location.

rpc APIGetMessages (APIRequest) returns (APIFeedResponse) {

option (google.api.http) = {

get: “/api/getMessages” // Option tells grpc-gateway that an HTTP

// GET to /api/getMessages should be

// routed to the APIGetMessages gRPC

// endpoint.

};

}

// Other endpoints omitted…

}

Protoc Generated Go Interfaces for YYAPI Service

The IDL above is then compiled to Go files by the protoc compiler to produce client proxies and server stubs as below.

// Client API for YYAPI service

type YYAPIClient interface {

APIGetMessages(ctx context.Context, in *APIRequest, opts ...grpc.CallOption) (*APIFeedResponse, error)

}

// NewYYAPIClient returns an implementation of the YYAPIClient interface which

// clients can use to call the gRPC service.

func NewYYAPIClient(cc *grpc.ClientConn) YYAPIClient {

// Code omitted for clarity..

}

// Server API for YYAPI service

type YYAPIServer interface {

APIGetMessages(context.Context, *APIRequest) (*APIFeedResponse, error)

}

// RegisterYYAPIServer registers an implementation of the YYAPIServer with an

// existing gRPC server instance.

func RegisterYYAPIServer(s *grpc.Server, srv YYAPIServer) {

// Code omitted for clarity..

}

Grpc-gateway Generated Go-code for REST Reverse Proxy of YYAPI Service

By using the google.api.http option in our IDL above, we tell the grpc-gateway system that it should route HTTP GETs for “/api/getMessages” to the APIGetMessages gRPC endpoint. In turn, it creates the HTTP to gRPC reverse proxy and allows you to set it up by calling the generated function below.

// RegisterYYAPIHandler registers the http handlers for service YYAPI to “mux”.

// The handlers forward requests to the grpc endpoint over “conn”.

func RegisterYYAPIHandler(ctx context.Context, mux *runtime.ServeMux, conn *grpc.ClientConn) error {

// Code omitted for clarity

}

So again, from a single gRPC IDL description you can obtain client and server interfaces and implementation stubs in your language of choice as well as REST reverse proxies for free.

gRPC — I heard there were some rough edges?

We started working with gRPC for Go late in Q1 of 2016 and there were definitely some rough edges at the time.

Early Adopter Issues

We ran into Issue 674, a resource leak inside of the Go gRPC client code which could cause gRPC transports to hang when under heavy load. The gRPC team was very responsive and the fix was merged into the master branch within days.

We ran into a resource leak in the generated code for grpc-gateway. However, by the time we found that issue, it had already been fixed by that team and merged into master.

The last early-adopter type issue that we ran into was around the Go’s gRPC client not supporting the GOAWAY packet that was part of the gRPC protocol spec. Fortunately, this one did not impact us in production. It only manifested during the repo case we had put together for Issue 674.

All in all this was fairly reasonable given how early we were.

Load Balancing

Now, if you are going to use gRPC this is definitely one area that you need to think through carefully. By default, gRPC uses HTTP2 instead of HTTP1. HTTP2 is able to open a connection to a server and reuse it for multiple requests among other things. If you use it in that mode, you won’t distribute requests amongst all of the servers in your load balancing pool. At the time that we executing the migration, existing load balancers didn’t handle HTTP2 traffic very well if at all.

At the time the gRPC team didn’t have a Load Balancing Proposal, so we burned a lot of cycles trying to force our system to do some type of client-side load balancing. In the end, since most of our raw gRPC communications took place within the data center, and everything was deployed using Kubernetes, it was simpler to dial the remote server every time thereby forcing the system to spread the load out amongst the servers in the Kubernetes Service. Given our setup it only added about 1 ms to the overall response time, so it was a simple work around.

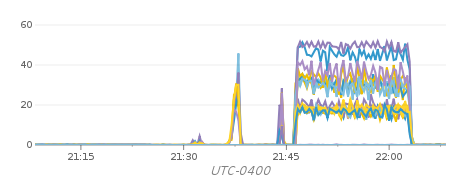

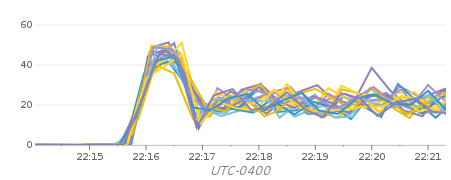

So was that the end of the load balancing issues? Not exactly. Once we had our basic gRPC-based system up and running we started running load tests against it, and noticed some interesting behaviors. Below is the per gRPC server CPU load graph over time, do you notice anything curious about it?

The server with the heaviest load was running at around 50% CPU, while the most lightly loaded server was running at around 20% CPU even after several minutes of warmup. It turned out that even though we were dialing every time, we had an nghttp2 ingress as part of our network topology which would tend to send inbound requests to servers to whom it had already connected and thereby causing uneven distribution. After removing the nghttp2 ingress, our CPU graphs showed much less variance in the load distribution.

Conclusion

REST APIs have their issues, but they are not going away anytime soon. If you are up for trying something a little cleaner, then definitely consider using gRPC (along with grpc-gateway if you still need to expose a REST API). Even though we hit some issues early on, gRPC was a net gain for us. It gave us a path forward to more tightly defined APIs. It also allowed us to stand up new implementations of the legacy REST APIs in GCP which teed us up to seamlessly migrate traffic from the AWS implementations to the new GCP ones in a controlled manner.

Having discussed our use of Go, gRPC and Google Cloud Platform, we are ready to discuss how we built a new geo store on top of Google Bigtable and the Google S2 Library — the subject of our next post.